‘The party that never stops’: British artist Sarah Lucas on The Colony Room Club, Soho

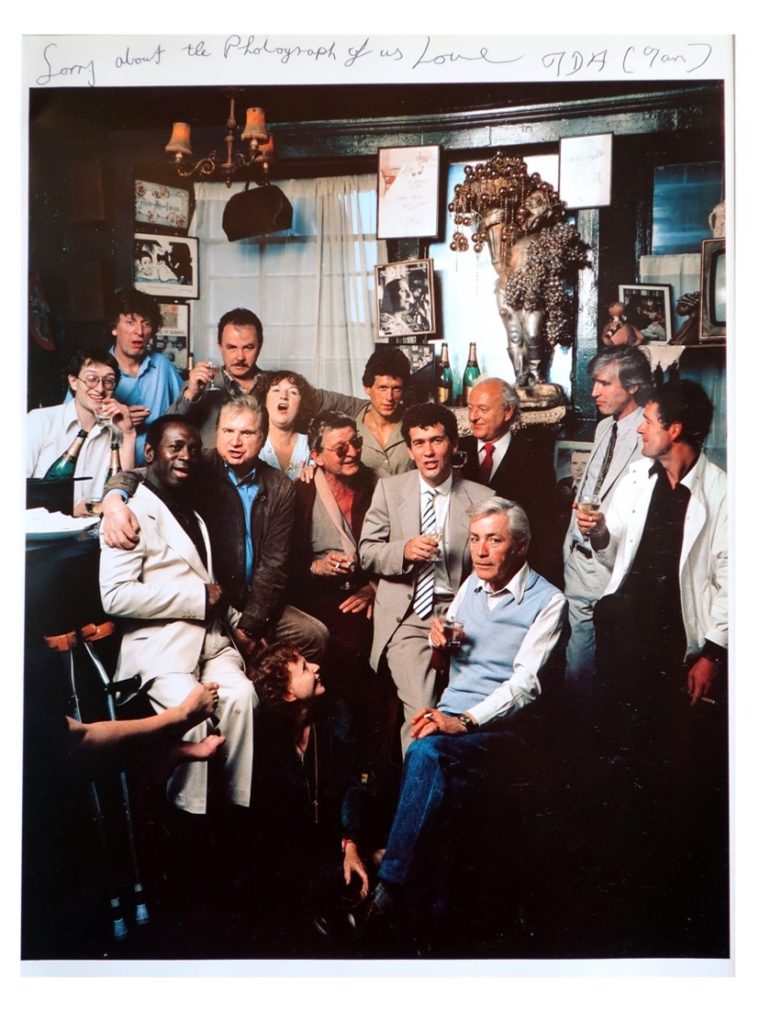

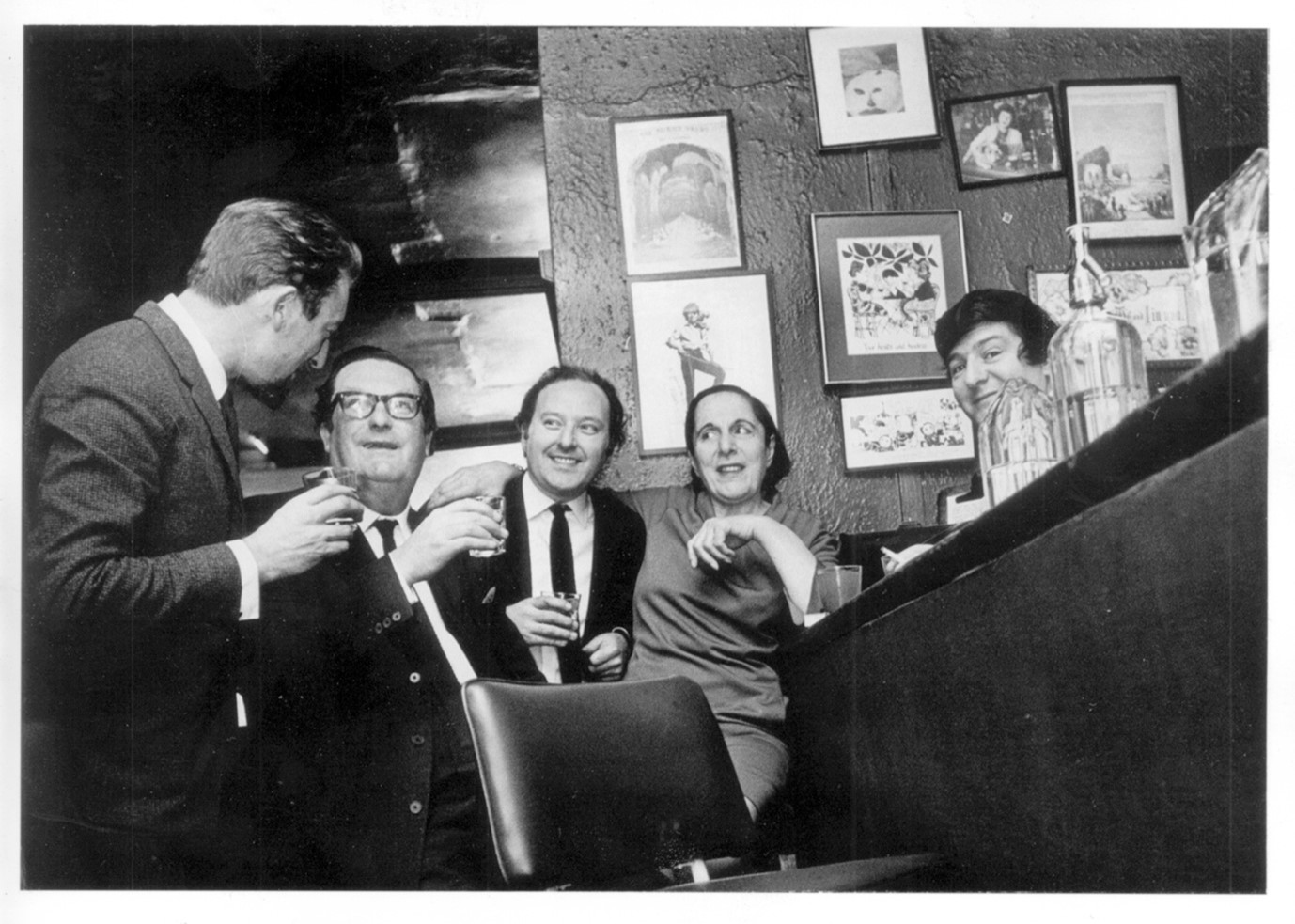

For more than sixty years, The Colony Room Club at 41 Dean Street, Soho, was a haven for artists, poets, radicals and free thinkers. The club attracted Soho’s artistic elite, including Francis Bacon, Lucien Freud, George Melly and Jeffrey Bernard, as well as people from aristocratic and political circles such as Princess Margaret, William Burroughs, David Bowie and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Bacon was a founder and lifelong member who helped to get rich patrons up its notoriously filthy stairs and into the room’s iconic green walls.

The club is currently being celebrated in a highly-acclaimed art exhibition, Tales from the Colony Room: Art and Bohemia, at Dellasposa gallery in Bayswater. The presentation comes hard on the heels of Tales from the Colony Room: Soho’s Lost Bohemia, an oral history of the club edited by Darren Coffield. In this exclusive interview, Coffield interviews artist Sarah Lucas about the Colony Room, its former proprietor Michael Wojas, and the Sebastian Horsley, both of whom died within weeks of one another in 2010.

DARREN COFFIELD: Everyone who frequented the Colony Room Club can clearly remember the first time they went there. Like the recipient of a major shock stumbling upon a murder scene, the club left its mark all who entered. Everyone has their own peculiar story of how they came across the club. During its sixty-year history, more romances, more deaths, more horrors and more sex scandals took place in the Colony than anywhere else, and if they didn’t happen there, they were definitely planned there. Can you remember how you first came across the club, Sarah?

SARAH LUCAS: I can’t remember at all the circumstances that led me to the Colony. No idea what I was doing before or after. I was with Damien Hirst and Angus Fairhurst (I imagine) and we popped in. It was dingy, green and crowded. Also smoky. Ian Board was behind the bar insulting people and swearing as they came in. I thought he was horrible. Someone said, ‘He’s alright when you get to know him.’ I thought, I’ll bear that in mind. I didn’t go back for a long while. By that time Ian was dead. He was still there in the form of his sculpted head which contained his ashes. Michael Wojas said that you can roll a pinch up in a cigarette and smoke him if you like.

The next time I clearly remember being there, it was just Michael sitting in an empty club wondering what he could do to get it going again.

DC: It was bizarre. For example, walking in one afternoon, the person working behind the bar had their back to me but seemed strangely familiar. Then, as they spun round, I was amazed to find it was you! How on earth did you get that gig?

SL: I wasn’t a member or habitué of the club at all, but one evening I went along. Naturally enough, I got completely drunk. I was talking with Michael and found myself saying, ‘I’ll come and do the bar one day a week.’ I have a lot of good ideas when I’m pissed. I try and live up to them. So the following Tuesday I duly arrived, and did it every Tuesday for a year. The day started at the traditional time, three o’clock, generally a fairly quiet time. Longer standing members would come in. Ray (last name escapes me – but he’s in your book) would come by for a vodka and lavish water, that alcoholic’s tipple. It was a good moment for chat. By six o’clock more people would have made it up the stairs. Peter Brunton would take his seat at the bar. Still a preponderance of old members at that time of day. Later in the evening the so called ‘young’ artists would start rolling in. There was a bit of an us and them feeling initially. Big Eddi [Suggs’ Mum] could be quite hostile to the new crowd. When I started I had the misguided idea I might drink less on the serving side of the bar. That didn’t happen. It always turned into a party.

DC: It was a non-stop party scene. After the Colony we’d wander down to Gerry’s (club) stay there to 3am (or later) – then to a hotel – drink the mini bar dry – then back to the French by 12 noon and drink until 3pm when the Colony re-opened and the whole cycle started again. The longest I’d go was 72 hours continuous partying, without sleep. Luckily for me, the urge to create was always stronger than the urge to drink, so I would naturally get to a point where my resolve to paint took over and I would have to bail out for the sake of my sanity. Quite a lot of artists who drank in the club, like Francis Bacon, would work for long intense periods and then splash the cash in the club when the work sold and the money came through. Others got bogged down, stayed too long and suffered from the local malaise ‘Sohoitis’ – a particularly contagious condition. The symptoms are drinking too much and talking about all the great ‘works’ you plan to create but never actually doing anything to achieve them. It really is a euphemism for the squandering of talent and youth. Needless to say all the people I used to hang out with are now either dead or in limbo (Alcoholics Anonymous). Both of which I’ve so far successfully managed to dodge…. but sooner or later you’d get pulled back in by the siren’s call and crash upon the rocks.

SL: Your account corresponds closely with my own experience. Occasionally I’d decide to have a quiet night in only to find myself leaving the house at two or three in the morning and heading into Soho to catch up with the action. It became an addiction. The party that never stops. I started to spend more and more time in Suffolk to slow it down a bit, but for the first couple of years it used to catch up with me even here. I miss it sometimes, the madness. But yeah, glad to have dodged the total ruin.

DC: Part of the allure of the club was the extraordinary people you came across there. One member flew half-way round the world to get nailed to a cross and publicly crucified. You went too. What on earth was that about?

SL: Sebastian Horsley? I didn’t know him all that well at the time. We’d seen each other at the club and I’d been over the road to his place once or twice for post-club carryings on. We were chalk and cheese us two. Him the total dandy and me the jeans and t-shirt, lank hair, no make-up. And that goes for personality too – the whoremonger and the radical feminist. But we amused each other. For all his pretensions he was very honest. We had a laugh.

He invited me for lunch at the French House. There was something he said he wanted to discuss, but it didn’t emerge until we’d finished eating and were already pretty drunk. He told me about the trip he’d been planning for some time, to go to the Philippines to get himself crucified. He said some people do that over there as a ritual. His girlfriend was supposed to go with him to film it but she’d now decided it was a bad idea and would I go instead? So I said, alright.

It wasn’t that I thought it was a good idea. I thought it was bloody stupid like a lot of his stunts, but I admired his bravery about them. He said he needed to do extreme things when he wasn’t taking drugs – needed the hit off them. Everyone I mentioned it to said ‘DON’T GO’. Some because they were concerned for my safety, others . . . I detected a particular antipathy to the idea in men, other artists. They really hated it. That tickled me.

Anyway I’d said I would go, so I did. Another bloke came with us, Dennis Morris the photographer. He was doing the still shots and me the video. The three of us arrived at a very seedy area of Manilla. Filthy, and prostitutes everywhere. Slightly ominous. Fortunately, that wasn’t where we were staying. Sebastian had a driver lined up and we were whisked away to a resort by a beach somewhere. One of these places with a fence all around it so that locals can’t get in. Our driver, Steven, had managed to get us some weed from somewhere and we sat on a veranda smoking and getting a little high and decided to drive into the local town and find a bar. By the time we got there we were completed stoned, couldn’t even stay on our chairs in the bar. We were all over the place crawling on the floor and laughing. It was the only time I’ve ever seen Sebastian smoke dope. Very funny. So we thought we’d better get ourselves back to the camp. We sat around on the veranda again, and Sebastian and Dennis kept talking about the penalty for drugs in the Philippines being death by execution. I started to get paranoid, I was thinking, fuck, we’ve all come to get crucified. It got so bad I couldn’t be with them. I took the weed and flushed it down the toilet.

Next day there was a feast for us at the Mayor’s house – a rambling, slightly decrepit, wooden house. The feast was laid out on a long table on the veranda, swarming with flies. The whole thing was quite solemn with the six-inch nails for Sebastian’s crucifixion passed around in a glass jar for everyone to see, and they didn’t look too hygienic either. We also met the Marys – three young girls who would do the wailing at the foot of the cross.

Early the next morning we left for the crucifixion site. When we got there the whole area was flooded. We made our way over in punts accompanied by the Marys, dressed in cheap, flowing, silky material, and a gaggle of curious locals staring at us holding the camera equipment up out of the water. Dennis kept saying, on a loop, ‘Whatever happens keep filming.’

Sebastian had on some sort of loin cloth he’d put together. The cross was lying on the ground and had a little platform for his feet. The nails were produced and he laid down on the cross. I saw him flinch when they banged the nails in but he didn’t cry out. Gradually, they got him up vertical on the cross. Once he was up there, you could see he was going in and out of consciousness with the pain. Suddenly there was a cracking sound. The platform couldn’t support his weight and he started to slide. Panic started. Everybody rushing about, no idea how bad it might be. He was down on the ground, ashen faced, ashen bodied, bloodied and unconscious. I kept filming. Weirdly it helped me not completely lose it. They were getting the nails out and he started to stir. He thanked them, always very polite. Luckily the six-inch nails hadn’t ripped his hands apart. Miraculous really. Sebastian, however, was disappointed as the whole thing only lasted ten minutes. He was pleased with his scars though.

DC: Sebastian very much wanted to be a ‘Soho face’ and running the last of the great afternoon drinking clubs, the Colony Room, Michael Wojas became a fulcrum of the social scene. He was a psychiatrist, counsellor, banker and a good friend to many people. Sebastian was drawn to Michael and the club like a moth to a flame. In its entire sixty-year history the club had just three proprietors: Muriel Belcher, Ian Board and Michael Wojas. It had been handed down from barman to barman, as one died another took up the baton. Running the club wasn’t like a 9 to 5 job, it was a vocation, like being a priest. It certainly wasn’t done for the money. There wasn’t much time for a private life outside the club. Michael had seen what running the club had done to Ian Board and knew the consequences. The work was relentless and there was no retirement fund. You literally died on the job. Michael wanted to get out before it killed him too – so, after twenty-seven years of working at the Colony, he decided to call last orders for the final time and closed the club on its 60th anniversary in December 2008. He died just 18 months later, aged just 53.

SL: The last time I saw Michael, he was up here for a midsummer party I gave. He was pretty shaky then and had a lot of trouble staying on his feet. In very jolly spirits though. Having fun in the sun.

The coffin! I can be very thick. When I was asked to make Michael’s coffin I thought I’d make a cardboard one. I’ve made quite a few coffins art-wise but this time I thought I’d better check on the size they’re supposed to be. I found a WikiHow about it. How to make a cardboard coffin and I followed the instructions. I have to admit I did think that something about it didn’t seem right but I’d run out of cardboard by then so it would just have to do. I suppose it was very slap dash of me in the gravest of circumstances.

It was picked up from me and the next I saw of it was on the day of the funeral. A motorbike and sidecar hearse had been booked to get him to the crematorium, but there was no way the coffin was going to fit in, much too wide in the shoulder – so it was loaded on to a white Transit van instead. I was so embarrassed. Anyway it got there. We were all in the Chapel and it was a lovely service and everyone was sad but in good spirits, singing, all drinking and raising a glass, and when it got to the time the conveyor belt starts and the coffin begins its journey toward the fire, it wouldn’t fit through the hatch! Oh my God. Everyone laughed uproariously. I was mortified. Eventually it had to be carried back out of the chapel, much foot stamping and clapping, and delivered round to the back door. Memorable. It still makes me blush.

Later, when I thought of it, I realised I was most probably asked to make it because everyone would have liked a cigarette coffin. That just didn’t occur to me and no one asked. I expect they just took it for granted that it would be coffin covered in cigarettes. Instead it wasn’t even a proper coffin. It was some WikiHow-Wild-West-Halloween cartoon coffin.

DC: That was such a strange summer. Rather like this one, it had an eerie unsettling feeling. The places and people you’d took for granted were taken away one by one. Michael and Sebastian were such good friends until Michael decided to shut down the Colony Room Club with Sebastian complaining, ‘Soho has lost it heart. The music has gone and the bars are being shut down like they are malaria joints.’ The campaign to save the Club became quite bitter. When Michael died, Sebastian remarked, ‘My mother taught me never to speak ill of the dead. Michael is dead. Good!’ Then the following week, after the premiere of his play, ‘Dandy in the Underworld’, Sebastian dropped dead too.

SL: I saw Sebastian the day before his show opened, at an opening for Maggi Hambling, on Albermale Street. Of course I had no idea that would be the last time I saw him. He’d often espoused the notion that if you come face to face with your doppelgänger you’ll die. Did the actor playing him do a very accurate job, I wonder. I thought it was a stunt when I first heard. I wouldn’t put that past him. Then I realised it was true.

Yes, a horrible week. Not sure Sebastian wanted to live much longer. He was very vain and hated losing his looks. On reflection I thought he had seemed a bit fed up with his lot that day before.

Legacy? Well I suppose it’s those who are still here. I imagine we’re all much the same in our scattered about orbits. Our personal clubs. Life is a club. What do you think? Did writing the book keep it alive for you – are you missing something now the book is finished?

DC: Looking back on it all now I realise that Bohemia was a borderless country, where the inhabitants tended to have untidy lives and even untidier deaths. As a club, the Colony Room was neither just a building, nor a location, it was an attitude to life, and although it evaporated long ago, people still travel to Soho in search of Bohemia, their heads more full of poetry than sense. Writing the book was incredibly cathartic. The oral history format really brought them all back to life, recounting their extraordinary lives in that tiny bar, and in the process I finally laid my ghosts to rest.

Tales from the Colony Room: Art and Bohemia, Dellasposa Gallery; until 20 December 2020.

www.dellsposa.com